- Council of the Great City Schools

- Historian, Philanthropist and 2021 National Teacher of Year Address Council

Urban Educator - November/December 2021

Page Navigation

- Urban School Districts Host Vaccination Clinics for Ages 5-11

- Changes at the Helm: NYC, L.A., and El Paso School Districts

- Historian, Philanthropist and 2021 National Teacher of Year Address Council

- Student School Board Members Aim to be Heard at Town Hall

- Miami School Board Member Named Top Educator

- Voters Decide on Education Ballot Issues

- Legislative Column

- Former Dayton Schools Superintendent; Fort Wort and Denver Board Members Remembered

- Baltimore Launches Student Learning Plans

Gates Urges Educators to Adopt a New Narrative of History

-

- Philanthropist Priscilla Chan Stresses Students Well-Being

- Teacher of the Year Seeks Joy and Justice in the Classroom

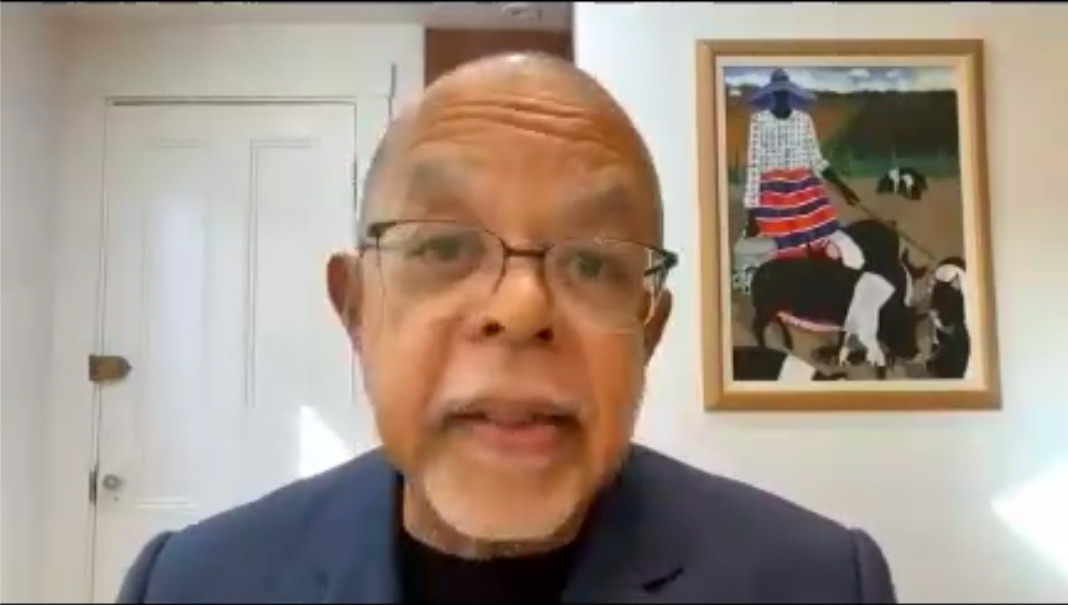

Henry Louis Gates Jr., the director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University, had a clear message for his audience of big-city school leaders: “respond responsibly” to critics and defend high school coursework in African-American history, Latino history, and ethnic studies.

“We have to integrate our courses, so that we’re not just dealing with Black history in February,” Gates said at the Council of the Great City Schools’ 65th Annual Fall Conference, which was held virtually. “And we have to integrate the narratives of Native Americans, women, gay people, and people of color into the larger stream and narrative flow of American history.”

Gates was joined in a conversation by Kelly Gonez, chair-elect of the Council and president of the Los Angeles Unified School Board, and Michael O’Neill, immediate past chair of the Council and vice chairperson of the Boston School Committee.

Gonez asked Gates how can school districts create a more inclusionary and truthful study of history in the nation’s classrooms?

The historian recommended seminars and curricular materials from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for use in an inclusive history curriculum and said that the organization is the gold star for curriculum development at all levels—from elementary to middle to high school.

And he also touted a free website, blackhistoryintwominutes.com, for teachers and young people that offers brief videos, which Gates and investor and philanthropist Robert F. Smith co-produced.

Gates, who has authored or co-authored 25 books and created 23 documentary films, noted that he is working with the College Board on developing the first Advanced Placement course on African-American history.

“We have to adopt a new narrative of American history in classrooms,” said Gates. The aim of the critics, he said, is “to keep us from integrating the story of America, and we have to integrate that story. We can’t act like we all landed on Plymouth Rock,” he quipped.

Gonez also asked Gates what should school districts keep in mind as they try to offer courses that better reflect the full history and culture of America.

“The most important thing,” answered Gates, “is that we have to make sure students know you don’t have to be Black to be an expert on Black history, you don’t have to be Hispanic to be an expert on Latinx/Latino history. … Every subject is teachable, every subject is learnable. If someone tries to say that a white man or woman is not qualified because they’re white to teach a subject related to Black people, that is a racist idea, and those of us in academia have to stand up against that that kind of political correctness. Any attempt to police speech in the classroom, we have to oppose – any attempt.”

O’Neill asked Gates to share lessons learned from Gates’ acclaimed PBS series, “Finding Your Roots,” the most popular show on PBS with an audience of 2.4 million.

“The political subtext is that we are all descended from immigrants,” Gates answered. “Your ancestors came because of the great potato famine, mine came in chains.”

Another lesson, he noted, is that genome testing shows humans are 99.9 percent identical in genetic makeup. “We are all in this together. We are descended through evolution from the same ancestral tree.”

Even the topic of slavery has more complexity than what students typically learn, he said.

If he were to create a unit on race, Gates said he “would start with the fact that slavery is inextricably intertwined with the history of civilization – beyond race. It’s not a Black and white thing only.”

Again and again, Gates took the long view: He observed that by the time Africans were forcibly shipped to the Americas, “slavery was thousands of years old – in China, in India, in the Middle East, in Eurasia, wherever. In Africa, Africans enslaved each other. … No one is innocent; we’re all guilty, we’re all complicitous.” Studying Black history in America, he said, “is about understanding the history of civilization.

He suggested reading “Slavery to Freedom,” the textbook written by John Hope Franklin, now in its 10th edition and rewritten by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a colleague of Gates at Harvard. “That is the bible of Black history,” he said.

During his address, Gates also discussed the importance of Reconstruction, the period following the Civil War between 1865 and 1877 when Black people experienced more freedom and rights than at any other time before in American history.

The historian has worked to shed light on this unique period of history by producing a prize-winning PBS miniseries, “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War”, and a bestselling companion book, “Stony the Road.”

According to Gates, Reconstruction was America’s first experiment with interracial democracy and the issues that were raised during Reconstruction have never been resolved.

“Understanding Reconstruction and its rollback is pivotal to understanding the history of race relations in America and especially attempts at voter suppression” even to this day, he said.

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000