- Council of the Great City Schools

- Districts Scramble to Deliver Meals During Crisis

Digital Urban Educator- April 2020

Page Navigation

- Miami’s Early Preparation Pays Off in Launch of Distance Learning

- Dallas Makes Smooth Transition to At-Home Learning

- Long Beach Ramps Up Professional Development for Remote Learning

- Austin Turns to Buses to Provide Internet Access

- Districts Scramble to Deliver Meals During Crisis

- Long Beach Promotes Jill Baker to Top Post, Albuquerque Names Interim

- Philadelphia Superintendent William Hite Stresses the Importance of 2020 Census

- Six Urban Schools Ranked Among The Nation’s Top 10

- Urban Teachers Receive $25,000 Milken Award

- Milwaukee Voters Approve $87-Million Referendum

- Top Magnet Schools in U.S. Named

- Urban Districts Named Best in Music Education

Districts Scramble to Deliver Meals During Crisis

-

With the aim of ensuring student – and staff -- health and well-being, the nation’s urban school districts had to pivot and, in many instances, pivot again to run emergency meal operations in the wake of school closures due to the Covid-19 crisis.

Some districts were forced to suspend or modify meal deliveries when food handlers fell ill. In one such district, Missouri’s Kansas City Public Schools, community groups stepped into the breech to distribute meals while the district redoubled sanitizing wipe-downs.

A Kansas City worker tested negative for the virus, and schools superintendent Mark Bedell took to social media to share the good news: “I’m excited to share that we are prepared to once again distribute school meals to our students!” he said.

Grab-and-go bags – the most common method of delivering breakfast and lunch when cafeterias are closed – was the go-to approach in many districts in the early weeks but variations emerged to streamline meal delivery for an effort with no end in sight.

Key revisions aimed to minimize not only person-to-person contact but also the time families spent waiting in line for meals during hours students otherwise might be engaged in distance learning.

Multiple meals were being bundled for pickup or delivered once or twice a week, rather than daily. Delivery points were being moved out of school buildings to kiosks in parking lots or at curbside.

Districts tapped bus drivers to deliver prepackaged bags or boxes of food along the routes they follow when school is in session. Minnesota’s St. Paul Public Schools opted to package five days of selected food items into one box, which drivers distributed on a designated day on their morning routes. That meals-on-wheels plan lasted a couple of weeks, then was scrapped as the district announced a plan to do direct delivery to students’ homes.

St. Louis Public Schools shifted to once-a-week distribution of kits with meals for seven days.

In San Antonio, students or guardians could pick up multi-day bundles, even including supper, at numerous curbside locations three days a week but the district also identified apartment complexes housing large numbers of students as drop-off points. Bus drivers were enlisted to deliver meals to those sites and also to their regular student pick-up stops across the city. There also was a plan for the drivers to distribute instructional materials.

“It’s real cool,” Nathan Graf, transportation director for the San Antonio Independent School District, told a local news station. “It’s a partnership between our district’s child nutrition program and transportation services. We call it SAISD Eats.”

Indianapolis Public Schools opted to deliver multiple prepackaged meals twice weekly at several school parking lots and two apartment complexes. The district also was coordinating expanded food distribution with a local food bank.

Numerous rules related to safety, hygiene and physical distancing were promulgated and widely publicized with notices on site, on the web and through other types of social media.

Texas’ Fort Worth Independent School District moved from daily distribution to two days a week, a change it said was aimed “at improving the safety of all involved” by reducing gatherings of parents and students and reducing employee interaction. The move also “promotes more parent and student engagement in online instruction daily versus the need to pick up meals daily,” according to the district website.

Detroit Schools Community District opted to distribute meals in bulk on fewer days and at fewer sites after some workers tested positive.

In Texas, some school districts began partnering with the Baylor University Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty to deliver shelf-stable foods directly to households through a program called Meals-to-You. The collaborative also created a website https://www.covid19txfoodresources.org/ identifying sites across the state where food for children was being distributed.

The Food Research & Action Center in Washington, D.C., published a spreadsheet of the different models that U.S. districts have adopted to deliver meals to students. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/18r1lKXwrDxExJ0dG7mqHuRrY7Nxk7SihBIqo84zLzsY/edit#gid=0

Meal distribution emerged as a key function and an ongoing challenge for districts in the days and weeks since schools were shuttered. According to the nonprofit School Nutrition Foundation, 30 million students depend on school meals as a key source of nutrition – a number that likely is significantly higher in the current crisis.

“School nutrition professionals have been working around the clock to ensure vulnerable students don’t go hungry during COVID-19 school closures,” Julia Bauscher, the group’s board chair, said in a statement.

Bauscher, who is director of school and community nutrition services at Kentucky’s Jefferson County Public Schools, took note of the scramble to find ways to safely serve meals to students. The Arlington, Va., based foundation began awarding grants to districts for equipment, supplies and such items as mobile carts and kiosks. “We want to support our school nutrition heroes as they work to reach more students with healthy meals during this crisis,” she said.

The emphasis was on best practices in food safety, according to Daniel Elinor, Jefferson County’s assistant director at the nutrition service center. Early on, the district obtained personal protective gear for all staff including goggles and masks for kitchen workers.

The startup of the effort was in double time. “We had to put the brakes on the train of the supply engine of doing hot meals and then turn left and do cold, individually wrapped meals,” Elinor said in an interview with FoodService Director magazine. For his district, like countless others across the country, the first week was akin to “reinventing the wheel hourly.”

As demand increased, the Jefferson County school system added sites at churches, apartment complexes and the YMCA, among other places. According to district officials, 500,000 meals have been distributed since March 16.

Partnering with Other Organizations

With great need apparent in many communities, districts embraced contributions from foundations, businesses and individuals and found ways to coordinate with other emergency food operations in their locales.

Atlanta Public Schools offered bagged meals and even “shelf-stable” grocery goods at selected sites, distributed food via buses and partnered with the nonprofit group Goodr, which accepts surplus food for rapid distribution to families in need.

Kansas City Schools compiled and published an extensive spreadsheet identifying clinics, churches and community groups that were distributing meals. https://www.kcpublicschools.org/meals

In Seattle, food bank volunteers filled bags to distribute to families for weekend needs at sites established by the district.

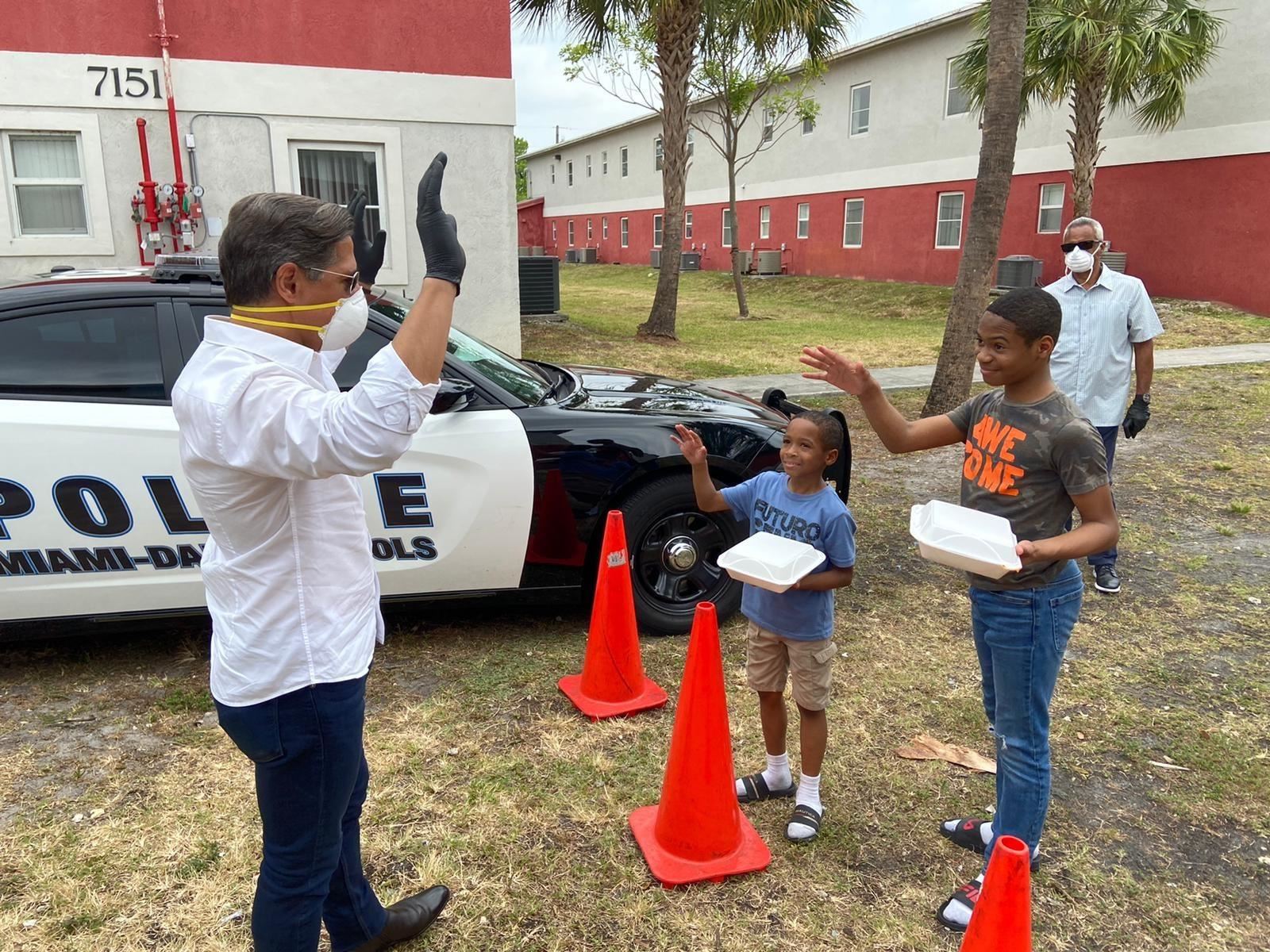

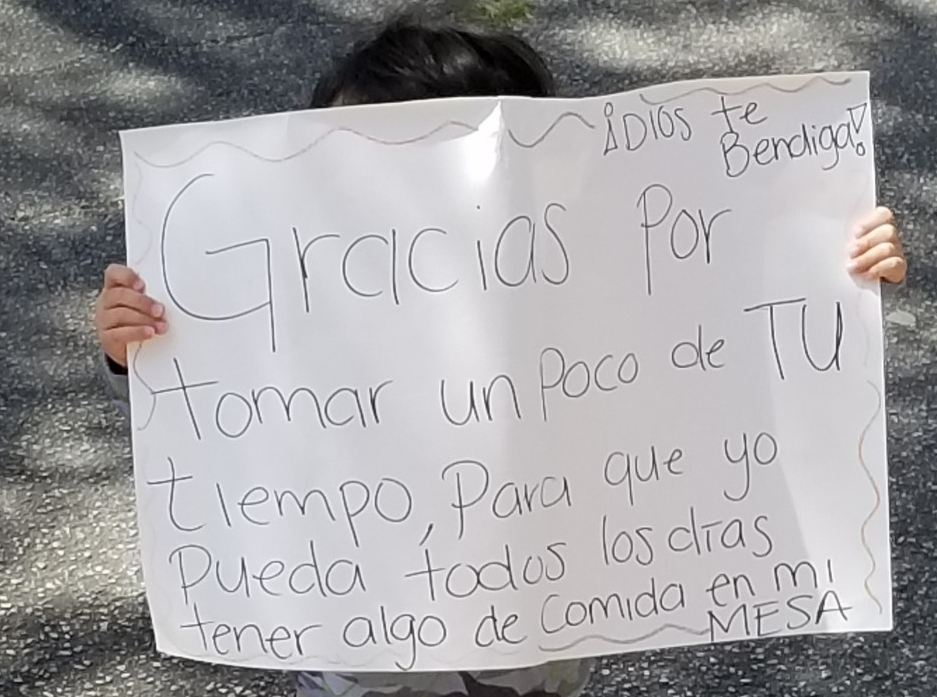

Miami-Dade County Public Schools distributed grab-and-go meals at 50 sites late in the day – from 4 to 7 p.m. – to avoid disruption to “ensure that the virtual instructional day is not interrupted.”

The district also touted success in its partnership with community partners including restaurateurs to deliver fresh-cooked hot meals as well as bags of fresh produce to homes in what the district described as its “most fragile communities.” Three-quarters of the district’s 350,000 students receive free or reduced-price lunch, and food insecurity is an issue among families in South Florida.

Otto Perez, owner of the Diced restaurants, told the Miami Herald he decided to donate 200 meals a day for two weeks to the Family Meals-on-the-Go program because, as a Cuban immigrant child, he grew up poor in Miami and qualified for free school lunches. Diced’s typical kids’ meals with cubed chicken, rice, black beans, lettuce and chopped tomatoes were being delivered at three migrant camps.

“I am middle class now, but I was a Cuban rafter,” Perez told the Herald. “I was one of those migrant kids.”

Touting multiple ongoing efforts, Miami Schools Superintendent Alberto Carvalho took to social media on multiple occasions.

“No child shall go hungry on our watch,” he tweeted.

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000